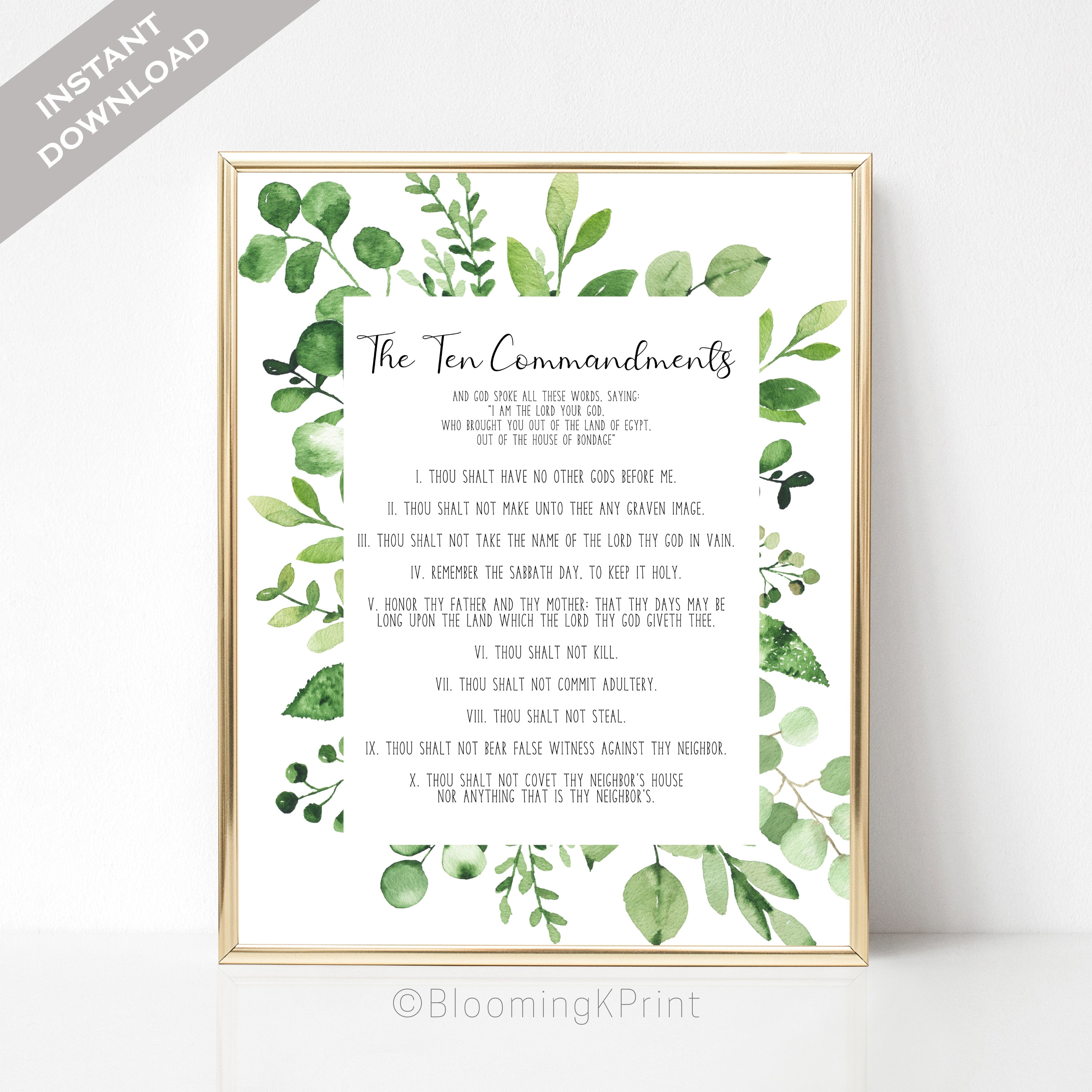

But which day the ‘Sabbath’ refers to has itself depended on whether you’re a Jew or a Christian: the Sabbath is traditionally regarded as Saturday in Judaism, but on Sunday in Christianity.Deuteronomy 4:13 chapter context similar meaning "And he declared unto you his covenant, which he commanded you to perform, even ten commandments and he wrote them upon two tables of stone." Deuteronomy 4:13 KJV copy save And he declared unto you his covenant, which he commanded you to perform, even ten commandments and he wrote them upon two tables of stone.Įxodus 34:28 chapter context similar meaning "And he was there with the LORD forty days and forty nights he did neither eat bread, nor drink water. Of course, what both versions have in common is the injunction to keep the Sabbath holy, the implication being that man shall not toil on that day. It states (5:15): ‘And remember that thou wast a servant in the land of Egypt, and that the LORD thy God brought thee out thence through a mighty hand and by a stretched out arm: therefore the LORD thy God commanded thee to keep the sabbath day.’ Indeed, Deuteronomy gives a quite different reason from Exodus: oddly enough, the reason, the exodus. Protestants, meanwhile, begin the list at ‘no other gods’ but then have ‘no graven images’ as the second commandment.Īnd even when it comes to keeping the Sabbath holy, there is some divergence of interpretation: Exodus states that followers should remember the Sabbath, while Deuteronomy has the slightly different keep or preserve in place of remember.Īnd whilst it’s commonly assumed that the reason for preserving (or remembering) the Sabbath is because God rested on the seventh day of Creation, only the Exodus version says as much (20:11: ‘For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it’). Roman Catholics, for instance, tend to regard ‘no other gods’ and ‘no graven images’ as part of the same commandment, since there is, indeed, some overlap. But even within Christianity, there is some disagreement about how the first few commandments should proceed. Swenson is helpful here, telling us that whilst Judaism considers ‘I am the LORD thy God’ to be the first commandment, Christians tend to view it as a preface to the first commandment (the one about having no other gods before Yahweh). What were these ‘ten commandments’? They include a range of decrees, including more practical guidance: ‘Thou shalt make thee no molten gods’ (34:17) ‘the firstling of an ass thou shalt redeem with a lamb: and if thou redeem him not, then shalt thou break his neck’ (34:20) and ‘Thou shalt not offer the blood of my sacrifice with leaven neither shall the sacrifice of the feast of the passover be left unto the morning’ (34:25).īut if we return to the list of Ten Commands provided in the summary above, there are some curious things to note about the numbering. And he wrote upon the tables the words of the covenant, the ten commandments.’ Nor are they even called ‘commandments’: the word used in most English translations of the original Hebrew text is ‘words’, hence the alternative name for the Ten Commandments: the Decalogue.īut confusingly, although the sections of the Bible which gave us the list now known as the Ten Commandments don’t call them ‘commandments’ or number them as ten, another passage from the Old Testament contains a list of instructions called ‘the ten commandments’, which have nothing to do with the list we now know.Įxodus 34:28 reads: ‘And he was there with the LORD forty days and forty nights he did neither eat bread, nor drink water.

As Swenson observes, it is ‘religious tradition’ that is responsible for our talking of ‘the Ten Commandments’.

There are many more than ten commandments in the Leviticus chapter, but even the versions in Exodus and Deuteronomy aren’t numbered as a clear list of ten. However, the Leviticus commandments are more numerous, including prohibition against making fun of those who are physically disabled (19:14 reads ‘Thou shalt not curse the deaf, nor put a stumblingblock before the blind’) and the famous rule about not wearing two different fabrics together (19:19 reads ‘thou shalt not sow thy field with mingled seed: neither shall a garment mingled of linen and woollen come upon thee’). The first two of these are the ones we tend to know, and are clearly where the list now known as the ‘Ten Commandments’ was derived from. Of course, there are instances in the Bible where all of these things are treated with less than respect, but the moral meaning of the Ten Commandments is fairly clear.Īs Kristin Swenson points out in her endlessly informative A Most Peculiar Book: The Inherent Strangeness of the Bible, there are in fact three biblical versions of the Ten Commandments: Exodus 20:2-17, Deuteronomy 5:6-21, and Leviticus chapter 19.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)